“Portrait painting is a reasonable and natural consequence of affection.”

— Samuel Johnson

A most urgent matter

In 1942, the art dealer and socialite Lois Shaw opened a gallery in midtown Manhattan, its purpose to find oil painters for spendy patrons. Or as the New Yorker described it, “to induce in a prospective subject the conviction that the commissioning of a heroic three-quarter-length likeness is a most urgent matter.”

Five decades before the invention of the front-facing camera, Portraits, Inc. was the mid-century’s answer to a selfie studio. Shaw and her colleagues did a brisk trade in paintings in all styles.

Then, as now, oil portraits seemed an indulgence of the wealthy, but Lois Shaw was quick to defend them:

“Until a few years ago portrait painting was looked down on as a corrupt branch of art, in which the artist was forced to do nothing but slick, flattering likenesses of his subjects.…People have learned not to expect that sort of prettiness nowadays.”

I mention this enterprise — which continues to this day, by the way, with locations now on the Upper East Side and in Flat Rock, North Carolina — for two reasons.

First, because Portraits, Inc. was recently mentioned in an excellent Bloomberg Business article with the provocative title “Getting Your Portrait Painted Is Trendy Again, and It’ll Only Cost You $15,000.”

The second reason?

Because commissioned portraiture has so many parallels with the work I do for Echo Storytelling Agency.

The stable expands: corporate storytelling

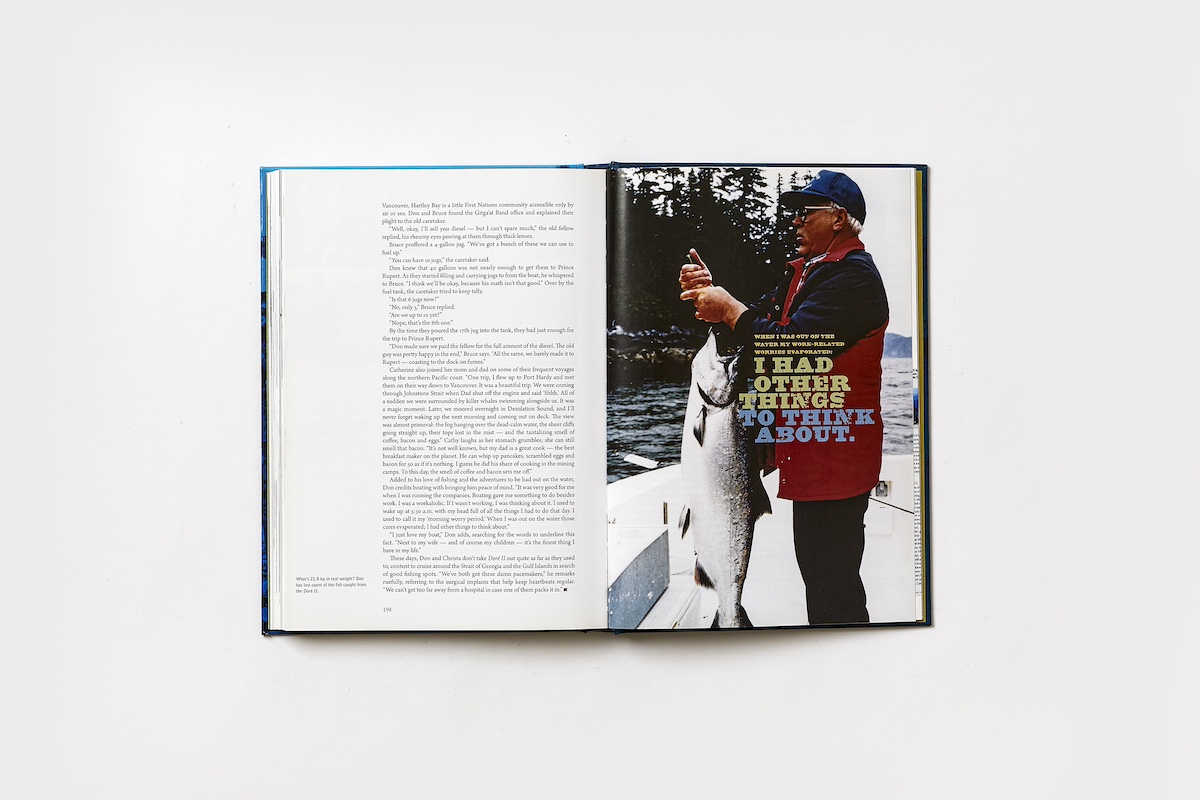

Today, ECHO’s client base is as varied as the work we’re engaged in, but the company began in 1999 as a publishing house solely for commissioned memoirs.

Those biographies, written by a small stable of professional writers, were modestly made and fiercely valued by the clients they documented. Those early patrons then helped ECHO move into corporate storytelling: they wanted to reproduce for their companies the positive experiences they had had “sitting” for their hard-bound portraits. ECHO’s writing stable expanded.

Now, more happy customers want to keep us working together — after all, a growing network has been deeply steeped in ECHO’s values-driven approach; with so many years of relationships formed, it only makes sense that clients ask us to help with further communication work.

And so ECHO has added a third space, not just telling stories of founders and of companies but engaging in digital work: optimizing web content, producing online videos and managing social media for businesses in many industries.

And it all began with portraits.

A bad rap

Why would anyone bother to commission a memoir?

The immediate, uninformed answer might be vanity. Only the vain would sit through days of interviews, the thinking goes, or read hundreds of pages reproducing their every thought.

Yet that hasn’t been my experience.

In fact, modesty is the bigger problem. Again and again, our clients turn aside questions: “It wasn’t that big a deal” or “That’s just what everyone was like back then.”

This has a lot to do with demographics: the Greatest Generation composes the bulk of our memoir subjects, and their modesty does seem remarkable by today’s standards. Which can make it tough to get them to share moments that would dwarf by orders of magnitude the “suffering” and “heartbreak” that celebrities bemoan on Buzzfeed.

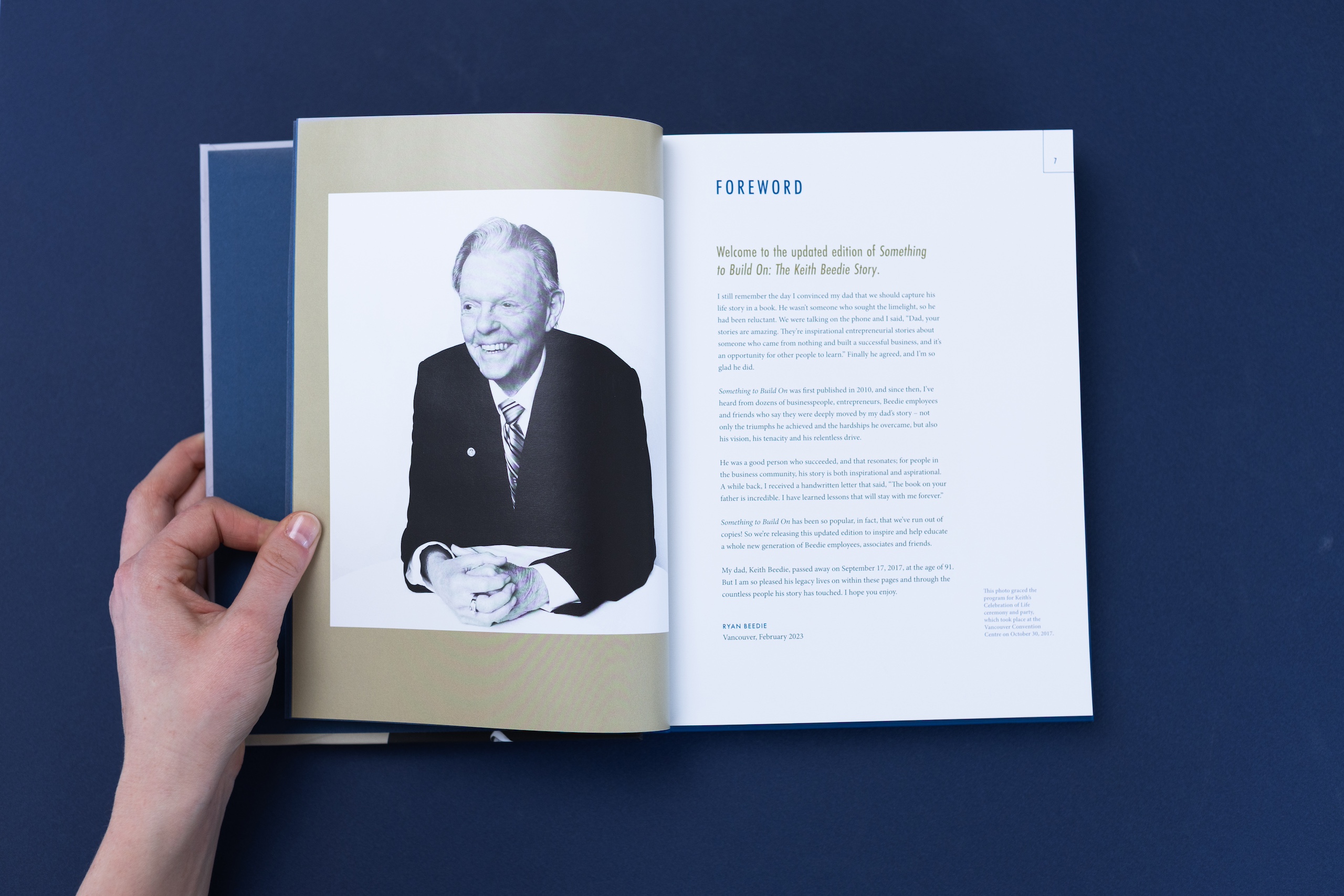

“I was extremely uneasy about doing a biography of my life. Well, I’m pleased to say that it has been accepted beyond my wildest expectations.”

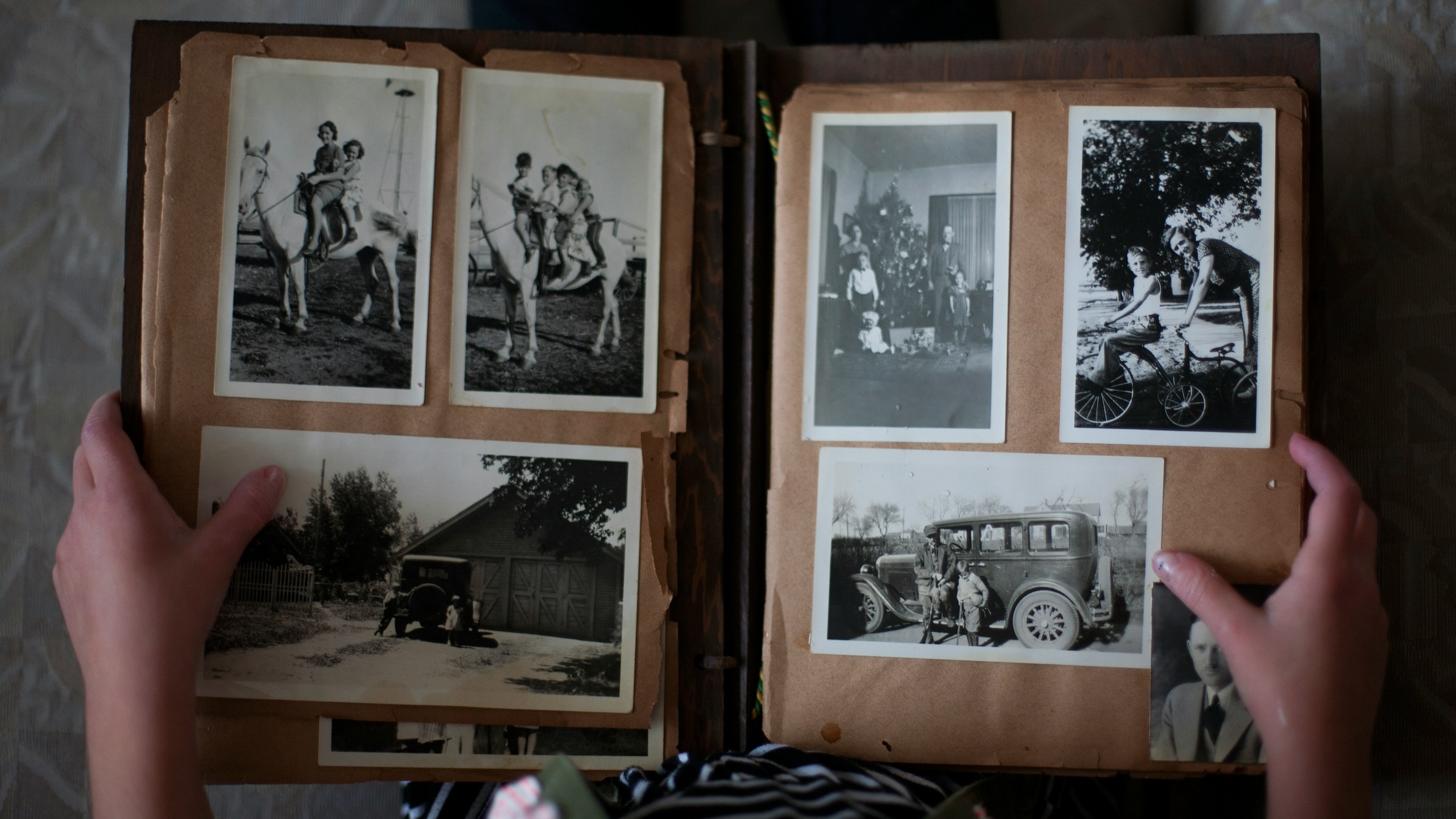

Several years back, the son and daughter of Canadian mining pioneer Don McLeod asked their dad to sit down for a memoir. At first he balked. As he said, “I simply didn’t see how anyone would be interested in my life story.” Yet over time, he came to look forward to the interview sessions as an enjoyable journey back in time.

The results delighted him: “I was extremely uneasy about doing a biography of my life. Well, I’m pleased to say that it has been accepted by family, friends and colleagues beyond my wildest expectations. As the word has started to get out, the demand for the book floors me.”

Why am I sitting here?

In Bloomberg, John Barrett hair salon CEO James Hedges IV talks about his reasons for hiring a painter — and not just any painter, but the transgressive TM Davy — to capture his portrait.

Far from vain (“How creepy would that be if I had an apartment filled with pictures of myself?”), he appreciates that the end product allows him a privileged peek into the creative process:

“If I were to ask TM if I could sit for 12 hours, watching while he paints, what’s the likelihood that would actually happen? I’m here, participating via this commission.”

This requires the luxury of time.

Portraits, be they painted or printed, take multiple sessions, each hours long, the artist and the subject in a room together, talking, opening up, sharing vulnerability. As the London-based painter Ralph Heimans said in the same article, the creative process here is:

“all about coming up with a personal statement about someone’s essence. In complete contrast with the selfie culture, which is all about the instant, the subjects are aware that this will last.”

The same devotion to process holds true for the people interviewed for our books. The writer and subject move across topics so personal, so emotional, so risky that many liken it to therapy.

For most, the investment is a gift — not to themselves, but to future generations, in partial answer to that most central question: Where did I come from, and where do I fit?

“Slow” portraiture reveals its value only over time.

The British painter Antony Micallef has called today’s era “an age of self-glorification and self-promotion [in which] we are little but advertisements for ourselves in shop windows.”

I hope and trust we at ECHO are able to swim against that current, rewarding our patrons with timeless, careful portraits infused with the very same qualities that made them remarkable in the first place.

Images by Danielle Campani and Jorgen Hendriksen (Unsplash).

Our team of storytelling experts know a thing or two about leveraging story for business, preserving legacy, and creating connections. Reach out to us today and tell us your story. It’s what we are here for.

John Burns is president of ECHO Storytelling Agency, where he pursues his highest personal values of service and utility, connecting the talents and passions of staff with the business hopes and challenges of his clients. And somehow, within all this, improving processes and efficiencies to maximize profitability. John spent over 20 years in journalism before joining ECHO, working in daily, weekly, and monthly publications and in radio.